I May Have Lived in the Wrong Era

Virginia’s John Tyler loved Shakespeare from an early age and would often quote or allude to him in public and private communications. Tyler had an elite background. His father had been Thomas Jefferson’s roommate at William and Mary. Tyler attended his father’s alma mater, beginning at the precocious age of twelve and graduating at seventeen. When he ran for vice president on the “hard cider and log cabins” ticket with William Henry Harrison in 1840, he tried to downplay this upper-class education. But he was well versed in music, poetry, and literature and collected an impressive library of 1,200 books.

Still, Shakespeare was Tyler’s favorite, and he felt comfortable citing the bard, knowing that his audience would understand him. In 1855, after he had moved on from the presidency to the role of “well-read elder statesman,” he gave an important speech on slavery and secessionism to the Maryland Institute. The speech was filled with literary allusions. He struck a note of optimism by making an apparent reference to Edgar Allan Poe, who had been a household name since the publication of “The Raven” in 1845: “I listen to no raven-like croakings foretelling ‘disastrous twilight’ to this confederacy …” He also made an adamant stand against secession, doubting that “a people so favored by heaven” would “throw away a pearl richer than all the tribe.” (His views on this subject would change after the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860, and he was a member of the Confederate Congress when he died in 1862.) His reference to Othello in the central point of his argument reflects his confidence that his listeners would share an appreciation for Shakespeare.

Tyler could quote Othello in a political speech because even his most simply educated countrymen were taught Shakespeare and because so many people went to the theater. Average Americans attended plays far more often than we might imagine. One nineteenth-century Massachusetts man managed to see 102 shows in 122 days. Not only must he have been a very determined theater-goer, but he must have had many opportunities. As Heather Nathans observes, “[t]hat he could find 102 opportunities in 122 days to be part of an audience underscores the importance of performance culture in America during this period.” The shows themselves were varied, including not just Shakespeare, but also singers, musicals, minstrels, and orators, both professionals and amateurs. Presidents, as well as regular citizens, both followed and attended.

Okay, so I wouldn't really want to live back in John Tyler's time, without all of the modern conveniences that are part and parcel of my life and which I completely take for granted. But wouldn't it be nice if modern-day "listeners" of political speeches "would share an appreciation for Shakespeare" that is worth writing about and commenting on? After all, elevated literary preferences might well indicate elevated preferences and expectations for other kinds of discourse, writing, speeches, and rhetoric--including political rhetoric. And the greater one's expectations for political rhetoric, the less patient one will be when politicians try to inundate one with taurine fertilizer as a substitute for elevated, meaningful and truthful rhetoric.

I don't expect politicians to ever fully stop trying to spread taurine fertilizer. But I do want it to be more difficult for them to do so. And in order to make it more difficult, we need a smarter, better educated citizenry; one that is willing to call politicians out when they are less than honest or exemplary with their words and their deeds. Until we get one, we can't expect politicians to live up to what is best in us.

A Folly We Are Determined to Commit

I am pleased that President Obama has decided to seek congressional approval prior to using military force in Syria. One does not know whether the president will go ahead and use force in Syria even if Congress disapproves, but at the very least, if he does so, he should be all alone in the endeavor.

Unfortunately, it would appear that some in the Republican leadership have decided not to leave the president alone. Both Eric Cantor and John Boehner have decided to give the president's Syria adventure their backing, and presumably, they will help the White House round up votes for a military mission that won't change a thing on the ground, that Assad knows he can ride out (because we have shouted from the rooftops that it will be limited in scope), and that is being embarked upon primarily in order to make us feel like we have tried to do something in order to stop the bloodshed in Syria. I am glad that Mitch McConnell remains skeptical--though I fear that at some point, even his skepticism will give way to what may at the very least be a reluctant endorsement--but the congressional Republican leadership failed to uniformly disapprove of what is very likely to be a military/foreign policy misadventure, one with only one ally--France--and not "dozens" of them. George W. Bush's "coalition of the willing" was much more coalesced, much more willing, and certainly larger than Barack Obama's is.

Just as much of the congressional Republican leadership deserves to be taken to task for its decision to endorse the Syria misadventure, much of the center-right punditocracy class deserves a trip to the woodshed as well. Jennifer Rubin seems to think that people who recognize that the United States has no strategic interest in intervening in Syria are "isolationists." This is entirely silly. Refusing to enter the Syrian civil war has nothing whatsoever to do with telling Bashar Assad to kill as many people as he wants. It has nothing to do with telling other dictators that they can feel free to use chemical weapons as well. Rather, it has to do with the fact that the United States has no strategic interest in entering the Syrian civil war and that it has no good way in which to bring about a positive change in Syria without possibly putting boots on the ground. And as that is the case, it is futile to waste time, materiel, and possibly lives in bombing the Syrian regime and its facilities for two or three days--and no more, as we have repeatedly reminded Assad--just so that we can pat ourselves on the back and claim that "we're not isolationists." Incidentally, last I saw, many of the people opposing the Syria misadventure are perfectly content to remain in NATO, like engage in an international liberalized trade regime, and would have been willing to continue to engage militarily in Afghanistan and Iraq, where we actually do have national security interests at stake. I count myself among that group. Am I and are people like me still "isolationists"?

Bret Stephens--whose writing I normally like--also sounds the alarm about "isolationists," or "Robert Taft Republicans," though at least he is kind enough to admit that not all Republicans who oppose intervention in Syria are "isolationists." Still, the use of "Robert Taft Republicans" is silly, because it suggests a facile comparison between people who see no reason whatsoever to engage militarily in Syria, and Republicans of decades past who opposed intervening in World War II, engaging in NATO, and launching the Marshall Plan. The Stephensian argument appears to be as follows:

If (a), then (b) and (c)

where (a) is "opposing intervention in Syria," (b) is "opposing entry into World War II," and (c) is "opposing participation in NATO and the Marshall Plan." No one really has to make the argument that just because one adopts (a), one automatically becomes the intellectual descendant of those who adopted (b) and (c) back in the day, right? No one really has to make the argument that just because one adopts (a), one would have adopted (b) and (c) if one could travel back in time, do we? Because if time really does have to be taken to make that argument to the masses and to reject Bret Stephens's faulty logic, then I despair for humanity.

It's bad enough that we appear to be committing to a military mission that will be useless at best, and will set back our tactical and strategic objectives at worst. It is even worse that we are doing it with transparently bad logic and bad arguments as our justification.

Someone Please Listen to Ramesh Ponnuru

Comme d'habitude, he makes a lot of sense:

Newt Gingrich is telling Republicans not to fear a government shutdown because the last one went so well for them. This is pure revisionist history, and they would be fools to believe him.

Some Republicans are urging the party to refuse to back any legislation to keep the government operating unless funding for President Barack Obama’s health-care overhaul is stopped. Other Republicans say this tactic will fail, citing the conventional wisdom that the government shutdowns of 1995-96 helped President Bill Clinton and hurt congressional Republicans.

The former speaker of the House is off message, or rather is revealing a contradiction in the political strategy of his current allies. Their public line is that any shutdown would be the unfortunate product of Democrats’ obstinate refusal to give in to the Republican demand to defund Obamacare. But it’s not easy to convey that message when prominent Republicans are saying that shutdowns are good for their party.

More important, Gingrich’s current spin on the events of 1995-96 is just wrong. The election of a Republican Congress in 1994 put government spending on a lower trajectory, as the election of a Republican House did again in 2010. Whether the shutdowns contributed to that result is a different matter.

The irony, of course, is that Gingrich is a historian by training--as he so often reminds us. I can get better history lessons from a coffee table, and for that matter, so can the current batch of congressional Republicans.

The World Is Full of Extraordinary Surprises

For nearly two centuries, scholars have debated whether some 325 lines in the 1602 quarto edition of Thomas Kyd’s play “The Spanish Tragedy” were, in fact, written by Shakespeare.

Last year, the British scholar Brian Vickers used computer analysis to argue that the so-called Additional Passages were by Shakespeare, a claim hailed by some as the latest triumph of high-tech Elizabethan text mining.

But now, a professor at the University of Texas says he has found something closer to definitive proof using a more old-fashioned method: analyzing Shakespeare’s messy handwriting.

In a terse four-page paper, to be published in the September issue of the journal Notes and Queries, Douglas Bruster argues that various idiosyncratic features of the Additional Passages — including some awkward lines that have struck some doubters as distinctly sub-Shakespearean — may be explained as print shop misreadings of Shakespeare’s penmanship.

“What we’ve got here isn’t bad writing, but bad handwriting,” Mr. Bruster said in a telephone interview.

Claiming Shakespeare authorship can be a perilous endeavor. In 1996, Donald Foster, a pioneer in computer-driven textual analysis, drew front-page headlines with his assertion that Shakespeare was the author of an obscure Elizabethan poem called “A Funeral Elegy,” only to quietly retract his argument six years later after analyses by Mr. Vickers and others linked it to a different author.

This time, editors of some prestigious scholarly editions are betting that Mr. Bruster’s cautiously methodical arguments, piled on top of previous work by Mr. Vickers and others, will make the attribution stick.

“We don’t have any absolute proof, but this is as close as you can get,” said Eric Rasmussen, a professor at the University of Nevada, Reno, and an editor, with Jonathan Bate, of the Royal Shakespeare Company’s edition of the complete Shakespeare.

“I think we can now say with some authority that, yes, this is Shakespeare,” Mr. Rasmussen said. “It has his fingerprints all over it.”

How Curiosity Became Fashionable

Decisions, Decisions

I Didn't Serve with Dwight Eisenhower. I Didn't Know Dwight Eisenhower. Dwight Eisenhower Was No Friend of Mine. But Barack Obama Still Isn't Dwight Eisenhower.

Geoffrey Norman explains.

Shorter New York Times: “Filibustering Presidential Nominees on the Basis of Ideology Is Bad, Except When It Isn't”

From yesterday's New York Times editorial:

After years of growing Republican obstruction — legislation blocked, judicial candidates forced to withdraw, presidential nominations left to languish, government agencies rendered powerless by denying them leaders — Senate Democrats say they are finally ready to take action. Barring a last-minute deal, Harry Reid, the majority leader, said he would move to change the Senate rules on Tuesday to ban the filibuster for executive appointments.

This is a relatively modest step toward returning basic governance to the chamber. It does not change the 60-vote requirement that Republicans have made routine for virtually all legislation, perverting the majoritarian vision of the Constitution. It does not ban the filibuster for judicial nominees, though we wish it did because Republicans are still holding up too many federal court candidates.

Nonetheless, Mr. Reid’s move would be an extremely important reassertion of majority rule, finally allowing a president’s nominees to cabinet departments and other agencies to come to a confirmation vote. The president’s right to assemble an executive team without encountering ideological litmus tests from the Senate is fundamental, as history shows. From the Eisenhower to the Ford administrations, there were no filibusters of executive nominees. Over the next 32 years, there were 20.

From the New York Times, March 6, 2005:

he White House's insistence on choosing only far-right judicial nominees has already damaged the federal courts. Now it threatens to do grave harm to the Senate. If Republicans fulfill their threat to overturn the historic role of the filibuster in order to ram the Bush administration's nominees through, they will be inviting all-out warfare and perhaps an effective shutdown of Congress. The Republicans are claiming that 51 votes should be enough to win confirmation of the White House's judicial nominees. This flies in the face of Senate history. Republicans and Democrats should tone down their rhetoric, then sit down and negotiate.

President Bush likes to complain about the divisive atmosphere in Washington. But he has contributed to it mightily by choosing federal judges from the far right of the ideological spectrum. He started his second term with a particularly aggressive move: resubmitting seven nominees whom the Democrats blocked last year by filibuster.

And from the New York Times, April 17, 2003:

Senators opposing Priscilla Owen, a nominee to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, are considering a filibuster to head off her confirmation vote. Filibusters are an extreme measure in which a minority of senators block an issue from being voted on. But the system for picking judges, which should be a relatively nonpartisan effort to seat jurists who reflect broad American values, has broken down. Filibustering Judge Owen's confirmation would send the Bush administration two important messages: the president must stop packing the courts with ideologues, and he must show more respect for the Senate's role.

Does Chess Superiority Correlate to Global Superiority?

Quote of the Day

For every Southern boy fourteen years old, not once but whenever he wants it, there is the instant when it's still not yet two o'clock on that July afternoon in 1863, the brigades are in position behind the rail fence, the guns are laid and ready in the woods and the furled flags are already loosened to break out and Pickett himself with his long oiled ringlets and his hat in one hand probably and his sword in the other looking up the hill waiting for Longstreet to give the word and it's all in the balance, it hasn't happened yet, it hasn't even begun yet, it not only hasn't begun yet but there is still time for it not to begin against that position and those circumstances which made more men than Garnett and Kemper and Armstead and Wilcox look grave yet it's going to begin, we all know that, we have come too far with too much at stake and that moment doesn't need even a fourteen-year-old boy to think This time. Maybe this time with all this much to lose and all this much to gain: Pennsylvania, Maryland, the world, the golden dome of Washington itself to crown with desperate and unbelievable victory the desperate gamble, the cast made two years ago.

--William Faulkner, Intruder in the Dust. Today, of course, is the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg.

A Much Needed History Lesson on DOMA

Many of the Democrats celebrating the Supreme Court's decision on DOMA would have you believe that they opposed the law from the outset. Zenon Evans performs a mitzvah by reminding all and sundry of what those Democrats desperately want all and sundry to forget:

. . . In response to the ruling, Bill Clinton tweeted that he is “grateful to all who fought tirelessly for this day.” He also released an official statement condemning the discriminatory nature of DOMA. What Clinton failed to mention was that he signed the act into law.

He wasn't alone in his silence. Other leading Democrats who supported it include Vice President Joe Biden, who voted for DOMA as a senator. Sen. Harry Reid (Nev.), who said, “The idea that allowing two loving, committed people to marry would have a negative impact on anyone else, or on our nation as a whole, has always struck me as absurd,” also forgot to note that he voted for DOMA. Sen. Chuck Schumer (N.Y.) released a statement praising the forward thinking of the Supreme Court. “The march towards equality... moved forward again today... The Supreme Court did the right thing here and helps us understand that the march to equality in America is unstoppable.” He made no mention of the fact that he, too, voted for the act and against "the march to equality." Sen. Bob Menendez (N.J.) patted himself on the back: “As a member of Congress who signed the amicus brief urging this decision [to repeal DOMA], I am thrilled that the Supreme Court took a strong stand for marriage equality." Menendez saw no need to clarify that this was only after he voted for DOMA in the first place. Sen. Tom Harkin (Iowa) voiced his support yesterday saying, "I am glad that the court recognized that all American families deserve the same legal protections," but made no mention of why his point of view flipped.

As in so many such cases, it is as though some people believe that their past positions cannot be accurately Googled by others.

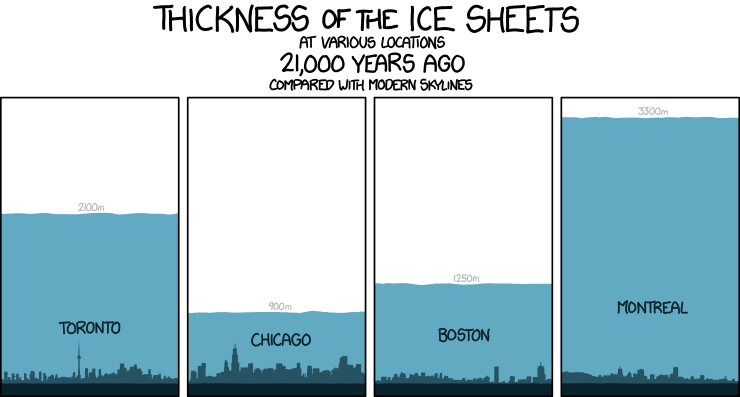

Your Favorite Cities, Back When They Were Submerged by Ice Sheets

Combating Terrorism: The Shultz Doctrine

Kenneth Anderson reminds us that much of our thinking on how best to combat terrorism comes from a speech given at the Park Avenue Synagogue in New York by then-Secretary of State George Shultz, who along with James Baker was the last great secretary of state we have had. Professor Anderson is kind enough to excerpt the salient aspects of Shultz's speech. I will pay forward that kindness by re-excerpting his excerpt:

We must reach a consensus in this country that our responses should go beyond passive defense to consider means of active prevention, preemption, and retaliation. Our goal must be to prevent and deter future terrorist acts, and experience has taught us over the years that one of the best deterrents to terrorism is the certainty that swift and sure measures will be taken against those who engage in it. We should take steps toward carrying out such measures. There should be no moral confusion on this issue. Our aim is not to seek revenge but to put an end to violent attacks against innocent people, to make the world a safer place to live for all of us. Clearly, the democracies have a moral right, indeed a duty, to defend themselves.

A successful strategy for combating terrorism will require us to face up to some hard questions and to come up with some clear-cut answers. The questions involve our intelligence capability, the doctrine under which we would employ force, and, most important of all, our public’s attitude toward this challenge. Our nation cannot summon the will to act without firm public understanding and support.

First, our intelligence capabilities, particularly our human intelligence, are being strengthened. Determination and capacity to act are of little value unless we can come close to answering the questions: who, where, and when. We have to do a better job of finding out who the terrorists are; where they are; and the nature, composition, and patterns of behavior of terrorist organizations. Our intelligence services are organizing themselves to do the job, and they must be given the mandate and the flexibility to develop techniques of detection and contribute to deterrence and response.

Second, there is no question about our ability to use force where and when it is needed to counter terrorism. Our nation has forces prepared for action —from small teams able to operate virtually undetected, to the full weight of our conventional military might. But serious issues are involved—questions that need to be debated, understood, and agreed if we are to be able to utilize our forces wisely and effectively.

If terrorists strike here at home, it is a matter for police action and domestic law enforcement. In most cases overseas, acts of terrorism against our people and installations can be dealt with best by the host government and its forces. It is worth remembering that just as it is the responsibility of the U.S. Government to provide security for foreign embassies in Washington, so the internationally agreed doctrine is that the security of our Embassies abroad in the first instance is the duty of the host government, and we work with those governments cooperatively and with considerable success. The ultimate responsibility of course is ours, and we will carry it out with total determination and all the resources available to us. Congress, in a bipartisan effort, is giving us the legislative tools and the resources to strengthen the protection of our facilities and our people overseas—and they must continue to do so. But while we strengthen our defenses, defense alone is not enough.

The heart of the challenge lies in those cases where international rules and traditional practices do not apply. Terrorists will strike from areas where no governmental authority exists, or they will base themselves behind what they expect will be the sanctuary of an international border. And they will design their attacks to take place in precisely those “gray areas’ where the full facts cannot be known, where the challenge will not bring with it an obvious or clear-cut choice of response.

In such cases we must use our intelligence resources carefully and completely. We will have to examine the full range of measures available to us to take. The outcome may be that we will face a choice between doing nothing or employing military force. We now recognize that terrorism is being used by our adversaries as a modern tool of warfare. It is no aberration. We can expect more terrorism directed at our strategic interests around the world in the years ahead. To combat it, we must be willing to use military force.

What will be required, however, is public understanding before the fact of the risks involved in combating terrorism with overt power. The public must understand before the fact that there is potential for loss of life of some of our fighting men and the loss of life of some innocent people. The public must understand before the fact that some will seek to cast any preemptive or retaliatory action by us in the worst light and will attempt to make our military and our policymakers— rather than the terrorists—appear to be the culprits. The public must understand before the fact that occasions will come when their government must act before each and every fact is known—and the decisions cannot be tied to the opinion polls. Public support for U.S. military actions to stop terrorists before they commit some hideous act or in retaliation for an attack on our people is crucial if we are to deal with this challenge. Our military has the capability and the techniques to use power to fight the war against terrorism. This capability will be used judiciously. To be successful over the long term, it will require solid support from the American people.

I can assure you that in this Administration our actions will be governed by the rule of law; and the rule of law is congenial to action against terrorists. We will need the flexibility to respond to terrorist attacks in a variety of ways, at times and places of our own choosing. Clearly, we will not respond in the same manner to every terrorist act. Indeed, we will want to avoid engaging in a policy of automatic retaliation which might create a cycle of escalating violence beyond our control.

If we are going to respond or preempt effectively, our policies will have to have an element of unpredictability and surprise. And the prerequisite for such a policy must be a broad public consensus on the moral and strategic necessity of action. We will need the capability to act on a moment’s notice. There will not be time for a renewed national debate after every terrorist attack. We may never have the kind of evidence that can stand up in an American court of law. But we cannot allow ourselves to become the Hamlet of nations, worrying endlessly over whether and how to respond. A great nation with global responsibilities cannot afford to be hamstrung by confusion and indecisiveness. Fighting terrorism will not be a clean or pleasant contest, but we have no choice but to play it.

Professor Anderson invites us to "consider what, if any, parts of [the Shultz speech] would not have been utterable by Obama administration officials and senior counsel today." I would respond by stating that unlike Barack Obama, George Shultz would never make the mistake of just unilaterally declaring the war on terror to be over, irrespective of the fact that terrorists haven't stopped attacking us.

Quote of the Day

One of the great history teachers in those days was a University of Chicago professor named Karl Weintraub. He poured his soul into transforming his students’ lives, but, even then, he sometimes wondered if they were really listening. Late in life, he wrote a note to my classmate Carol Quillen, who now helps carry on this legacy as president of Davidson College.

Teaching Western Civ, Weintraub wrote, “seems to confront me all too often with moments when I feel like screaming suddenly: ‘Oh, God, my dear student, why CANNOT you see that this matter is a real, real matter, often a matter of the very being, for the person, for the historical men and women you are looking at — or are supposed to be looking at!’

“I hear these answers and statements that sound like mere words, mere verbal formulations to me, but that do not have the sense of pain or joy or accomplishment or worry about them that they ought to have if they were TRULY informed by the live problems and situations of the human beings back there for whom these matters were real. The way these disembodied words come forth can make me cry, and the failure of the speaker to probe for the open wounds and such behind the text makes me increasingly furious.

“If I do not come to feel any of the love which Pericles feels for his city, how can I understand the Funeral Oration? If I cannot fathom anything of the power of the drive derived from thinking that he has a special mission, what can I understand of Socrates? ... How can one grasp anything about the problem of the Galatian community without sensing in one’s bones the problem of worrying about God’s acceptance?

“Sometimes when I have spent an hour or more, pouring all my enthusiasm and sensitivities into an effort to tell these stories in the fullness in which I see and experience them, I feel drained and exhausted. I think it works on the student, but I do not really know.”

--David Brooks.

Nothing Is Written

I enjoyed reading this book review of the great and good Paul Johnson's Darwin: Portrait of a Genius. The following passage was particularly arresting:

. . . Darwin was born into a highly literate and distinguished family, some members of which are the focus of biographical studies in their own right. He was the grandson of Erasmus Darwin on his father’s side, and of Josiah Wedgwood on his mother’s. It was a splendid inheritance. A successful medical doctor, Erasmus corresponded with Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Benjamin Franklin, and hobnobbed with Matthew Boulton, James Watt, Joseph Priestly, and other members of the Lunar Society. His Zoonomia was placed on the Catholic Index of forbidden books. Josiah was such a successful entrepreneur that Samuel Smiles wrote a book on him. Robert, Erasmus’s son and Charles Darwin’s father, married Susannah, Josiah’s oldest daughter. As was the case with many of the Darwin men, Robert was a closet freethinker and atheist. The Wedgwoods on the other hand were religious (Josiah was a staunch Unitarian).

Robert was another successful medical doctor and astute financier (money was invested rather than spent: sober thrift was a characteristic his son was to share). Thus Darwin was born into wealth, and adhered to the conservative values of the landed gentry. By all accounts a quiet, placid, even-tempered child, he was taught at home by his older sister Caroline before being sent, in 1817, to a local day school; in 1818, when he was nine, he was moved to the Shrewsbury Grammar School. The classics were wasted on the young schoolboy – he was brought up in a household which spent much time outside, fishing, hunting, gardening; his own preferences are seen in his father’s sharp words, “You care for nothing but shooting, dogs and rat-catching, and you will be a disgrace to yourself and all your family.”

In 1825, now sixteen, he was packed off to Edinburgh – a “purgative” in the words of Desmond and Moore – in order to follow the family tradition and study medicine. He spent two years there before throwing in the towel (a wonderful anecdote is of the lectures on anatomy in which the professor repeated, word for word, the lectures his own grandfather had delivered over a century before – including asides such as “When I was a student in Leiden in 1719”).

Since a medical career was out of the question, his father decided a career in the church might be suitable. Himmelfarb says that Robert “respected neither the clergy nor his son enough to credit them with any profound religious convictions”. Darwin entered Cambridge, and embarked on the three-year education that would qualify him for a clerical career in the Anglican church. While preparing for ordination, he read and enjoyed William Paley’s Natural Theology. He also came across Alexander von Humboldt’s Personal Narrative of a Journey to the Equinoctial Regions of the New Continent. And he developed interests in beetles, botany, and geology. On the surface at least unambitious, and certainly genial and unassuming, he seems to have drifted through Cambridge, although he was befriended by some of the young professors, most notably John Stevens Henslow and Adam Sedgwick.

He appeared to be set on a life as a botanising country clergyman. However, on graduation in 1831, after returning home to prepare for the first day of the shooting season, he found awaiting him a letter from Henslow, who had recommended him as naturalist for a scientific expedition, to be commanded by a Captain Robert FitzRoy RN, which was to survey the coasts of South America and Tierra del Fuego. Then a young captain, FitzRoy wanted a gentleman companion as much if not more than a naturalist, and Darwin, while not yet a qualified naturalist, was certainly a gentleman. If he accepted, he would circumnavigate the globe, be away from home for what was initially thought to be two years, and be provided with countless opportunities to engage in fieldwork in botany, zoology and geology. Suspecting, in Himmelfarb’s words, that beetle-collecting was not much of an improvement on rat-catching, his father opposed the idea – his feckless son seemed to be determined to turn his back on yet another career – and so Darwin, with regrets, initially declined the offer. However a Wedgwood uncle was not only in favour, but willing to plead his case. Permission was given, and he hastily wrote to accept the offer.

He was to embark on the HMS Beagle, today surely one of the most famous of all British naval vessels. Originally a three-masted, 235-ton Cherokee-class ship – a class known as “coffin brigs” because they had a tendency to sink in bad weather – she had just returned from a five-year voyage, and had to be rebuilt, adding seven tons and a higher upper deck. After some false starts, she successfully set sail from Plymouth Sound in December 1831. Darwin had previously promised FitzRoy to view the planned departure date as the starting date of his “second life” and to celebrate it “as a birthday for the rest of my life”. It certainly made him who he was.

In what might be related news, the following is possibly worth noting:

This Post Is Dedicated to Readers Who Are Politicians

I don't ever want to hear or read about how you supposedly have it rough because of attacks on you from 24/7 cable TV shows, or because of criticism from the blogosphere. I can guarantee you that one particular politician who arrived on the scene long before you did had it far rougher than you ever will in terms of having to deal with criticism and carping:

By nearly any measure—personal, political, even literary—Abraham Lincoln set a standard of success that few in history can match. But how many of his contemporaries noticed?

Sure, we revere Lincoln today, but in his lifetime the bile poured on him from every quarter makes today’s Internet vitriol seem dainty. His ancestry was routinely impugned, his lack of formal learning ridiculed, his appearance maligned, and his morality assailed. We take for granted, of course, the scornful outpouring from the Confederate states; no action Lincoln took short of capitulation would ever have quieted his Southern critics. But the vituperation wasn’t limited to enemies of the Union. The North was ever at his heels. No matter what Lincoln did, it was never enough for one political faction, and too much for another. Yes, his sure-footed leadership during this country’s most-difficult days was accompanied by a fair amount of praise, but also by a steady stream of abuse—in editorials, speeches, journals, and private letters—from those on his own side, those dedicated to the very causes he so ably championed. George Templeton Strong, a prominent New York lawyer and diarist, wrote that Lincoln was “a barbarian, Scythian, yahoo, or gorilla.” Henry Ward Beecher, the Connecticut-born preacher and abolitionist, often ridiculed Lincoln in his newspaper, The Independent (New York), rebuking him for his lack of refinement and calling him “an unshapely man.” Other Northern newspapers openly called for his assassination long before John Wilkes Booth pulled the trigger. He was called a coward, “an idiot,” and “the original gorilla” by none other than the commanding general of his armies, George McClellan.

One of Lincoln’s lasting achievements was ending American slavery. Yet Elizabeth Cady Stanton, the famous abolitionist, called Lincoln “Dishonest Abe” in a letter she wrote to Wendell Phillips in 1864, a year after Lincoln had freed the slaves in rebel states and only months before he would engineer the Thirteenth Amendment. She bemoaned the “incapacity and rottenness” of his administration to Susan B. Anthony, worked to deny him renomination, and swore to Phillips that if he “is reelected I shall immediately leave the country for the Fijee Islands.” Stanton eventually had a change of heart and lamented her efforts against Lincoln, but not all prominent abolitionists did, even after his victory over slavery was complete, even after he was killed. In the days after Lincoln’s assassination, William Lloyd Garrison Jr. called the murder “providential” because it meant Vice President Andrew Johnson would assume leadership.

Lincoln masterfully led the North through the Civil War. He held firm in his refusal to acknowledge secession, maneuvered Confederate President Jefferson Davis into starting the war, played a delicate political game to keep border states from joining the rebellion, and drew up a grand military strategy that, once he found the right generals, won the war. Yet he was denounced for his leadership throughout. In a monumental and meticulous two-volume study of the 16th president, Abraham Lincoln: A Life (2008), Michael Burlingame, the professor of Lincoln studies at the University of Illinois at Springfield, presents Lincoln’s actions and speeches not as they have come to be remembered, through the fine lens of our gratitude and admiration, but as they were received in his day. (All of the examples in this essay are drawn from Burlingame’s book, which should be required reading for anyone seriously interested in Lincoln.) Early in the war, after a series of setbacks for Union troops and the mulish inaction of General McClellan, members of Lincoln’s own Republican party reviled him as, in the words of Senator Zachariah Chandler of Michigan, “timid vacillating & inefficient.” A Republican newspaper editor in Wisconsin wrote, “The President and the Cabinet,—as a whole,—are not equal to the occasion.” The Ohio Republican William M. Dickson wrote in 1861 that Lincoln “is universally an admitted failure, has no will, no courage, no executive capacity … and his spirit necessarily infuses itself downwards through all departments.”

Charles Sumner, a Republican senator from Massachusetts, to whom Lincoln often turned for advice, opposed the president’s renomination in 1864: “There is a strong feeling among those who have seen Mr. Lincoln, in the way of business, that he lacks practical talent for his important place. It is thought that there should be more readiness, and also more capacity, for government.” William P. Fessenden, the Maine Republican, called Lincoln “weak as water.”

Of course, even if one is not a politician, there is a great deal that can be learned from Lincoln in how he dealt with the horrible attacks on him as a person and as a president--all the while leading the North to victory in the Civil War, preserving the Union, and ultimately working to free the slaves. The piece reports that Lincoln would privately respond to criticism by saying “I would rather be dead than, as President, thus abused in the house of my friends.” And yet, he persevered as president--to the country's great benefit. Whether or not we are in politics, there is much in Lincoln's example for the rest of us to emulate. Personal attacks are ephemeral. What endures is how we deal with the attacks, and what legacy we leave behind despite the jibes of critics and character assassins.

What the Chinese People (Shockingly) Don't Know

June 4th was the 24th anniversary of the Tienanmen Square massacre. NPR reports that thanks to Chinese government censorship, a lot of people know very little about the history of the massacre:

. . . it's important to remember that a lot of people here have some familiarity with what happened 24 years ago, but a lot of people aren't that clear on it. For instance, I'll just give you an example. Back in 1997 when I first came to Beijing, I met a number of young women - they were in their 20's - and they were chatting with some American men. And the American men said, you know, we really respected what the Chinese did back in 1989 and that man standing up against those tanks.

And the women said: What man? What tanks? They hadn't actually ever seen that image. More people now, because the Internet is so big here, have seen it. But by and large, people aren't that familiar with what actually happened.

In China, Big Brother is winning.

Tumbling 'Round the Intertubes--May 26, 2013

1. We are doomed.

2. Anyone really surprised by this?

3. Have I mentioned recently that we are doomed?

4. I mean, seriously, we are doomed.

In Memoriam: Boruch Spiegel

Would that we had more like him:

Boruch Spiegel, one of the last surviving fighters of the Warsaw ghetto uprising of 1943, in which a vastly outgunned band of 750 young Jews held off German soldiers for more than a month with crude arms and firebombs, died on May 9 in Montreal. He was 93.

His death was confirmed by his son, Julius, a retired parks commissioner of Brooklyn. Mr. Spiegel lived in Montreal.

The Warsaw ghetto uprising has been regarded as the signal episode of resistance to the Nazi plan to exterminate the Jews. The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum calls it the first armed urban rebellion in German-occupied Europe.

As a young man, Mr. Spiegel was active in the leftist Jewish Labor Bund, and when it became clear that the Germans were not just deporting Jews but systematically killing them in death camps like Treblinka, the Bundists joined with other left-wing groups to form the Jewish Combat Organization, known by its Polish acronym ZOB.

In January 1943, when German soldiers entered the ghetto for another deportation — 300,000 Jews had already been sent to Treblinka or otherwise murdered in the summer of 1942 — ZOB fighters fought back for three days and killed or wounded several dozen Germans, seized weapons and forced the stunned Germans to retreat.

“We didn’t have enough weapons; we didn’t have enough bullets,” Mr. Spiegel once told an interviewer. “It was like fighting a well-equipped army with firecrackers.”

In the early morning of April 19, the eve of Passover, a German force equipped with tanks and artillery tried again, surrounding the ghetto walls. Mr. Spiegel was on guard duty and, according to his son-in-law, Eugene Orenstein, a retired professor of Jewish history at McGill University, gave the signal to launch the uprising.

The scattered ZOB fighters, joined by a right-wing Zionist counterpart, peppered the Germans from attics and underground bunkers, sending them into retreat once more. Changing tactics, the Germans began using flamethrowers to burn down the ghetto house by house and smoke out those in hiding. On May 8, ZOB’s headquarters, at 18 Mila Street, was destroyed. The group’s commander, Mordechai Anielewicz, is believed to have taken his own life, but scattered resistance continued for several more weeks in what was now rubble.

By then, Mr. Spiegel and 60 or so other fighters had spirited their way out of the ghetto through sewers. One was Chaike Belchatowska, whom he would marry. They joined up with Polish partisans in a forest.

“He was very modest, a reluctant hero,” his son said. “He was given an opportunity, and he took it. I don’t think he was braver or more resourceful than anyone else.”

Oh, but he was plenty brave. The righteous do not always have material advantages over their enemies. But they have courage and goodness in abundance and for that alone, they will be remembered kindly by history.

And of course, the memory of the righteous is a blessing. Requiescat in pace.